Possibly my interest is based in my lack of early exposure to kid heroes when I was a kid. I was always primarily a Marvel reader, and Marvel didn't do sidekicks (apart from Rick Jones, who never did have a typical hero-sidekick relationship with any of the three heroes he used to hang with). When they did have teenage characters, they were not subordinate to an adult hero as in the case of Batman and Robin (as I recall them from the little Silver Age DC I did read). The X-Men were teenagers--in fact, their secret identities were those of students in a private school--and although Xavier was their teacher, it was the X-Men who did the battling, with only occasional aid from the Professor. And Johnny Storm, the Human Torch, was an equal partner in the Fantastic Four (certainly not the most mature partner, he was hot-headed and quick to fight, but then so was the Thing, a contemporary of Reed Richards). Spider-Man was also a teenager, and operated entirely on his own, associated with no older hero at all.

(I know that DC Comics has a far richer tradition of young heroes and sidekicks, but I have not read enough DC to comment intelligently on what they've done, so my discussion here is going to be limited to Marvel books.)

As I said, Marvel had younger heroes, but did not really have kid heroes. Mutants by definition were at least of teen age, because mutant powers did not typically activate until puberty. Other heroes tended to gain their powers via training or industrial accidents, situations less likely to apply to young kids.

And although Marvel/Timely's Golden Age kid sidekicks were clearly depicted as kids in the 1940s, later images of these heroes in flashback tended to age them.

For example, here's an image of Captain America's partner, Bucky, from a WWII-era comic, looking all of ten years old, if that (not that any specific age was ever given):

Here's a picture of Bucky from a Silver Age Captain America book (thank you, Marvel Essentials!). You'll notice that this Bucky is probably supposed to be at least thirteen or fourteen--still young, but now specifically a teenager:

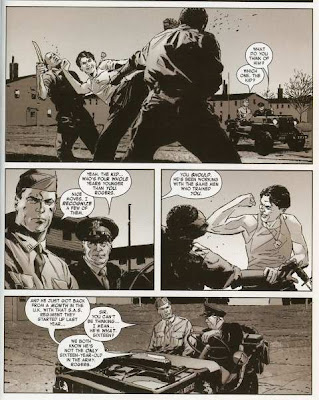

Finally, this series of panels from the recent Brubaker Winter Soldier storyline, when Cap is first introduced to the sixteen-year-old Bucky. The age is specifically given, and it's also mentioned that there were plenty of other sixteen-year-old soldiers in the army at this time (therefore, while Bucky is young, it's not culturally inappropriate for that time period):

You'll also notice how the responsibility for Bucky's becoming Cap's sidekick shifts over time. In the 1940s, it was Cap's idea! (This surprised me, although I suppose it shouldn't have--Cap is the adult, the authority figure, and it had to be his choice of who to work with.) By the 1960s, it was Bucky's idea and Cap went along with it because he really had no choice. And in 2005, neither Cap nor Bucky originated the plan, and although clearly Cap is more conflicted about it than Bucky, the idea belongs to the Army, who have authority over both Cap and Bucky.

The notion of kids running around together, having great (and perilous) adventures with no adult supervision, is one with a lot of history in the media. In the old days it was practically a movie genre of its own. No one ever asked where the Bowery Boys' parents were, after all, while they were wandering the streets all day and night. And for those less urban movie kids, excuses were made for parental absence: Nancy Drew's father traveled a lot, and her mother was dead. Any adventurous girls could practically be guaranteed a missing mother, because what mother would let her daughter roam the town unchaperoned? (Dads were allowed to be less careful, apparently.) Adventurous boys were more likely to have a mother, but she was never a strong figure, never able to keep her son from his gallivanting (unless of course the plot required it), and more often than not taking a "boys will be boys" attitude about the whole thing.

Easier still to make them all orphans, as was most often the case in comic books. The young hero only became a hero because of his (it was almost always a boy) association with an older hero. The older hero took on a fatherly or brotherly role, and there seems to be no objection from anyone to the younger hero entering dangerous situations. Even the frequent capture (and threatened torture) of the younger hero doesn't seem to give anyone a second thought. Besides, there's never really any worry, because the sidekick's mentor will always come to the rescue and save his young protege. The Golden Age kid sidekick is never operating on his own.

And even in a group situation--kid heroes working together--the adult heroes are often a presence, and you get the feeling that they'll certainly show up if and when the youngstes are in any danger they can't handle. Although I've not read any of the Young Allies books (are there any reprints of these comics?), here's a passage from All in Color for a Dime describing a typical issue:

Much more successful were The Young Allies, a kid gang headed by Bucky and Toro. The rest of the gang included the usual kid gang lineup: Tubby, the fat slob; Knuckles, the pugnacious kid from Brooklyn; Jefferson Worthington Sandervilt, boy inventor who vociferated exclusively in polysyllabic vocabulary--and Whitewash Jones, the inevitable minstrel-show caricature of a Negro, superstitious and watermelon-loving, with pendulous lips, bulging eyes, a zoot suit, and natural rhythm.

Their first adventure had them battling the Red Skull; being patted on the head by Hitler ("My! My! Vot nice Cherman boys!"), who didn't notice Bucky's costume, Toro's swimming trunks, or Whitewash's non-Aryan coloring; being imprisoned in a concentration camp; breaking out; flying to Russia, where they were nearly sent to Siberia; flying to China; returning to America, and being rescued by Captain America and the Human Torch. Whew!!

(During the course of the story, Bucky disguised himself as the Red Skull by painting an ordinary human skull red and putting it over his head. God knows how.) (1)

From what I can see, modern comics featuring teen heroes (pre-teen kid heroes seem to be much rarer) seem to operate in much the same way as they have since the 1960s--or they try to. The Young Avengers were a bit surprised to run into objections when they began fighting crime, particularly from the older then-ex-Avengers Captain America and Iron Man.

Cap of course would rather the hero business remain adults-only for personal reasons, but he does understand the concept. As for Iron Man, at this point he doesn't seem to have any kid-specific objections, and my impression is that if he could get away with keeping even those adults dear to him from going into battle, he would do it. Regardless, the kids do not get much support from the older heroes at this time, although eventually it does become apparent that they need to know how to use their powers because simply having these abilities makes them targets, and at the very least they need to know how to protect themselves. A far cry from jovially welcoming them to the team.

Since then--well, it's been so long since I've seen an issue of YA that I'm not entirely sure what's been going on with them. They seem to be somewhat active, and to have received some training, but of course Civil War has confused a lot of issues. Regardless, the group has not been thrilled at being discounted or held back because of their age.

The X-Men are no longer teenagers and have not been for some time; those students at Xavier's school who are underage are trained, but discouraged from entering dangerous situations (which would make for a pretty dull New X-Men title, if it weren't for the fact that dangerous situations just tend to happen to anyone associated with the X-Men).

The main thing, I think, is that as a culture we have become much more aware of the need for protecting our children, to the point where the average modern comic reader would find the freedom given the Young Allies (or even the early X-Men) difficult to accept. Nowadays, it's no longer a certainty that the hero will save the day and everything will be all right in the end. Comic book heroes die, are tortured, severely injured, crippled, violated, traumatized. If those things are possible for adult heroes, they are also possible for young heroes--and writers and readers may not be willing to condone that or even to show it.

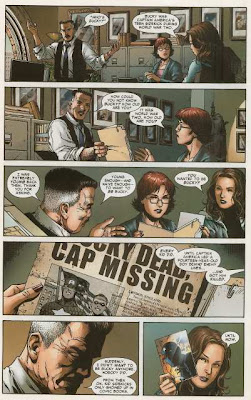

A good example of this shift is given here, where J. Jonah Jameson tells Jessica Jones (a one-time kid hero herself) about his own experiences as a kid during WWII, and the way public perception of kid heroes changed after the "death" of Bucky:

This is clearly a retcon (back in the 60s the only one complaining about teen heroes was Cap himself, and that seemed only to extend to his own unwillingness to work with kids anymore) but it does make some sense that the public would have shared the same assumptions that the older comic book audience did--that the hero would always come to the rescue, that the kid sidekick was never really in any danger because good would always triumph over evil--and that those assumptions could have been broken by the death of a young hero.

The real problem with Jonah's point is that the general public did not know that Cap and Bucky had disappeared at the time it happened--that's why the government supposedly brought in Jack Monroe and his mentor to be the 1950s commie-bashing Cap and Bucky, so that Cap's death in 1945 would remain a secret--so, yeah, there are huge holes in this idea, but it does have some validity in terms of what could have changed public opinion. (It does not work with the rest of Marvel continuity, unfortunately.) In reality, of course, it's been a far more gradual thing.

It does, in any case, seem to be a fairly universal opinion in the modern Marvel universe that minors should not be fighting crime. Even the Winter Soldier himself, a former kid sidekick and a man out of time with, presumably, a lot of outdated attitudes, seems uncomfortable with the idea of working with kid heroes.

On the other hand, from the context it could certainly be inferred that what he is questioning is their competence rather than whether it is appropriate for them to be out there in the first place. After all, his first inclination is to "let them take it out" on their own. That would seem to make more sense given his background--that while he might not ally himself with teenagers by choice, he probably wouldn't have the same objections to the concept as the modern world does.

1. Thompson, Don. "OK, Axis, Here We Come!" All In Color For A Dime, ed. Dick Lupoff and Don Thompson. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications, 1997. (Originally published in 1970.)

5 comments:

Hi there - nice blog!

Just a thought - do you think that the "ageing" of sidekicks is linked to the ageing of the target audience? In the Golden Age, most comics readers were pre-teens: now (other than the adults amongst us) the target demographic is teenagers. Therefore, the sidekicks for the "younger" reader to identify with get older too.

And it looks less creepy for grown men to be hanging out with teenagers than ten-year olds that aren't related to them, of course.

A very well-done post. It is intersting how the ages of the sidekicks and young heroes have changed and gotten older over the years. I believe that Alistair does have a point, there aren't a whole lot of little kids reading comics anymore, the audience tends to be older.

I can find it believeable that those old stories had kids running around unsupervised and having adventures...because the constant hovering of parents is a more recent phenomenom. When I was a kid, we didn't have computers or game boys or ipods, and our television was black and white. We went outside and played...all day. With the other kids in the neigborhood, or alone. My Mom knew more or less where we were, but it wasn't a case of going to ballet, to soccer, to karate, to whatever planned activity that they seem to do nowadays.

God, I'm dating myself.

Alistair - It's possible, particularly the giving of a specific age of 16 in the Brubaker story--modern comic audiences tending to be adults. (Kids or teens identifying with Bucky would probably prefer no specific age be given). Although the Bucky drawn in the early-90s Adventures of Captain America also looked to be in his later teens... That's a good point, although I think that modern sensibilities overall play a role as well.

My kids do like books featuring younger characters, but they're younger than the average comic reader (most kids' moms won't pay modern comic prices for something for their kids to read, I suspect).

Sally - If you're dating yourself, so am I, because I think you're right. When I was a kid, my brother and I spent lots of time running around the woods, building tree houses, etc., with no adult supervision. My mom didn't know where we were for hours at a time and that was fine, she didn't have to worry.

I don't let my kids do that (granted that that has something to do with the wolves and cougars that have moved into the area in the thirty years since I was a kid...). They do spend a lot of time outdoors, but they're always within yelling distance.

Great, thoughtful article! I'm finding so much more interesting stuff to read on the comics blogosphere these days than I do on the "mainstream" comic news sites.

As for Cap and Bucky, I've always gotten a kick out of that mask Steve Rogers is holding in the second Kirby-drawn origin (with the black and white art). Look at the size of that mask! It looks like a potato sack!

Oh, and as dangerous as it was for Bucky to accompany Cap into the heat of battle, there were some other aspects of Life With Cap that may not have been the greatest influence on young Buck:

Check it out here.

Mark - I've got that issue of Cap in a reprint (Marvel Masterworks, IIRC), and it's a hoot! You're right, too--Bucky complains a lot more about the Fauntleroy suit than Cap does about the corset and dress and heels. In fact, he looks pretty comfortable in that outfit... :)

Post a Comment